All Can Be Won by Eloquence That Even the Sword of Warring Enemies Might Gain

How to Persuade While the Other Person Does All the Talking

According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus, one of the greatest generals to ever live, frequently sought counsel from his ambassador, Cineas. As a student of the famed orator Demosthenes, Cineas was so skilled in persuasion that he often helped Pyrrhus conquer cities without bloodshed. In fact, Pyrrhus used to say

“More cities had been won for him by the eloquence of Cineas than by his own arms.”

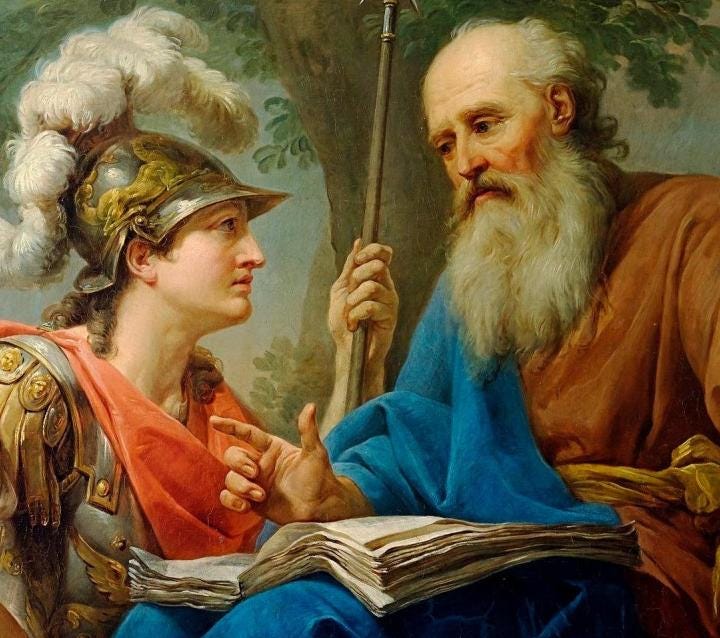

On the verge of Pyrrhus invading Italy and challenging Rome, Cineas recognized the flaws in his ambition and attempted to dissuade him. Using his efforts as a model, I’ll show how Socratic questioning1 and rhetorical softeners allow you to subtly probe others, uncover intentions, and exploit weaknesses in motivation.

Cineas began the conversation with a carefully posed question:

"The Romans, O Pyrrhus, are said to be good fighters, and to be rulers of many warlike nations; if, then, Heaven should permit us to conquer these men, how should we use our victory?"

And Pyrrhus said: "Thy question, O Cineas, really needs no answer; the Romans once conquered, there is neither barbarian nor Greek city there which is a match for us, but we shall at once possess all Italy, the great size and richness and importance of which no man should know better than thyself."

Although people rarely hesitate to answer a single question, softening the question with a rhetorical technique makes it less confrontational and, consequently, encourages the one answering to reveal more.

As an example, rather than simply asking his first question, Cineas also preceded it with social proof to ease tension while simultaneously implicating the difficulty of Pyrrhus’s plan. For, as the original Greek confirms2, he claimed “are said to be good fighters ” instead of “are good fighters”, and the difference, although subtle, provided the voice of others instead of Cineas’s alone.

Having opened up Pyrrhus, Cineas proceeded:

After a little pause, then, Cineas said: "And after taking Italy, O King, what are we to do?"

And Pyrrhus, not yet perceiving his intention, replied: "Sicily is near, and holds out her hands to us, an island abounding in wealth and men, and very easy to capture, for all is faction there, her cities have no government, and demagogues are rampant now that Agathocles is gone."

There is almost no technique more strategic than pausing after someone answers your question. If it doesn’t compel your counterpart to fill the silence, it at least signals thoughtfulness towards their response as Cineas demonstrated.

Repeat Their Last Three Words

An effective way to practice strategic silence is to mentally repeat the last three words of the other person’s answer. This forces you to comprehend their response while occupying the few seconds of quietness that often urges someone to volunteer more information.

Additionally, by slowing down conversation, this technique makes you less reactive. If you’re like me, you at times find yourself defaulting to reactive listening during difficult conversations. This behavioral pattern involves being so concerned with communicating your perspective that you immediately respond to or even interrupt the person across from you without assessing their words. When you focus on firing back, you ignore their words, so you miss critical insight, provoke defensiveness, and lose credibility. To break this habit, use the last three words repetition exercise, and see how it boosts your authority by giving you control of the tone and pace of the conversation.

The silence worked. Pyrrhus revealed more of his intent, so Cineas encouraged him to continue:

"What thou sayest," replied Cineas, "is probably true; but will our expedition stop with the taking of Sicily?"

"Heaven grant us," said Pyrrhus, "victory and success so far; and we will make these contests but the preliminaries of great enterprises. For who could keep his hands off Libya, or Carthage, when that city got within his reach, a city which Agathocles, slipping stealthily out of Syracuse and crossing the sea with a few ships, narrowly missed taking? And when we have become masters here, no one of the enemies who now treat us with scorn will offer further resistance; there is no need of saying that."

Instead of going directly to the next question, Cineas first conceded that Pyrrhus was probably right. However, rather than surrendering, he was being strategic. For when you consider the possibility of being wrong, even momentarily, you’re forced to test your argument more rigorously and strengthen it in the process. This intellectual courage makes you appear more rational while disarming your counterpart and inviting them to expand on their point.

After eliciting Pyrrhus’s lengthiest answer, Cineas cornered him:

"None whatever," said Cineas, "for it is plain that with so great a power we shall be able to recover Macedonia and rule Greece securely. But when we have got everything subject to us, what are we going to do?"

Then Pyrrhus smiled upon him and said: "We shall be much at ease, and we'll drink bumpers [3] , my good man, every day, and we'll gladden one another's hearts with confidential talks."

In response, Cineas amplified Pyrrhus’s argument extending it to further conquest. This amplification not only built a sense of agreement between the two, but, more importantly, showed conclusively what all his previous softeners had supported — Cineas was listening.

With respect to listening, you’re only a good listener if you appear to be one. While listening builds insight, appearing to listen builds goodwill. Just as people despise others ignoring them, they look favorably upon those who savor their every word. When someone feels heard, they lower their defenses. And when they lower their defenses, they’re easier to influence.

Having uncovered Pyrrhus’s intent, Cineas finally made his point:

"Then what stands in our way now if we want to drink bumpers and while away the time with one another? Surely this privilege is ours already, and we have at hand, without taking any trouble, those things to which we hope to attain by bloodshed and great toils and perils, after doing much harm to others and suffering much ourselves."

As with any persuasive attempt, Cineas must have prepared in advance for Pyrrhus’s potential responses and how he would address them. Therefore, it is likely Cineas was using the Socratic questions to both find answers and to best set up the exchange to make his point.

With this set up in mind, only after Pyrrhus’s response to the fourth question was Cineas able to present his point with maximum effect. Since his argument is mainly restating what Pyrrhus said, for the sake of cognitive consistency, Pyrrhus felt compelled to consider it:

By this reasoning of Cineas Pyrrhus was more troubled than he was converted; he saw plainly what great happiness he was leaving behind him, but was unable to renounce his hopes of what he eagerly desired.

Conclusion

Don’t dissuade yourself with Cineas’s failure, but instead use it as a lesson. If you’re looking to uncover truth in dialogue, asking Socratic questions led with rhetorical softeners will provide you with all the information you need.

Key Techniques:

Soften your questions to probe inoffensively.

Leverage silence and use the last three words technique to keep them talking.

Concede a point to lower their guard.

Amplify and restate their ideas to show you’re listening.

Thanks for reading! If you have alternative insights about the dialogue here or examples of how you used this technique, please leave a comment below.

If you have any dialogues, you’d like me to examine, please feel free to leave those in the comments as well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socratic_questioning

πολεμισταὶ μέν, ὦ Πύρρε, Ῥωμαῖοι λέγονται

Specifically, λέγονται is the 3rd person plural present passive indicative of λέγω, meaning “to name” or '“to call” when in the passive voice. Literally, “the Romans are called”

“Bumpers” are drinking vessels or large servings of wine